Mohammed Ayoob*

Kashmir is not one but two problems. There is the problem of Kashmir between India and Pakistan and the problem in Kashmir between the people and the Central government. The first is based on Pakistan’s challenge to the legality of the State’s accession to India; the second on the disaffection of the State’s population that has created a problem of legitimacy for the Indian Union. If the political elites had the sagacity to solve or at least manage the problem ‘in’ Kashmir, the problem ‘of’ Kashmir would have lost its salience over time. Unfortunately, they did exactly the reverse.

Pakistan, unsurprisingly, fished in troubled waters by infiltrating ISI-trained terrorists into the Valley and by training Kashmiri militants to attack Indian forces. This mayhem further strained the Kashmiris’ relations with the Centre.

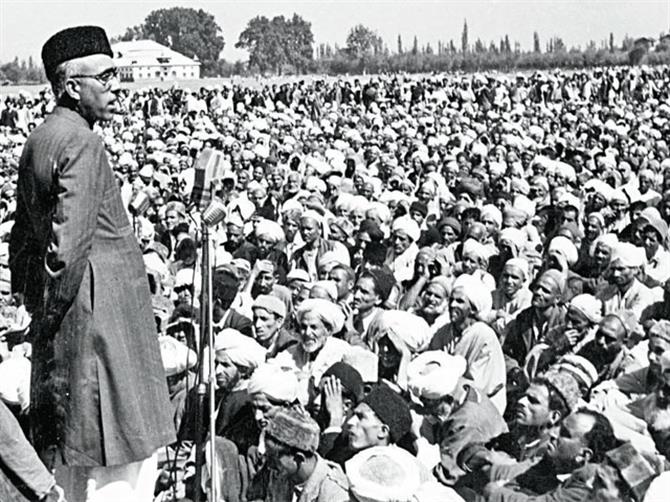

It was essential that Kashmir’s special status be recognised in the Constitution because of the extraordinary circumstances surrounding its accession and because it defied the communal logic on which Partition was based. Unfortunately, Hindu communal forces, led by the Jan Sangh, began agitating from 1950 for the removal of Article 370. This had a major psychological impact on the Valley’s population and on Sheikh Abdullah who, in the face of considerable opposition, had convinced the Kashmiri Muslim elite that their fate was more secure with India than with Pakistan.

Abdullah’s removal from power and imprisonment in 1953, on the suspicion that he was hobnobbing with the Americans to create an independent State, was a major blow to the legitimacy of Indian rule in Kashmir. The principal proponents of this idea, Karan Singh and Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad, had their own reasons — the first to avenge his father and the second to become the Chief Minister of the State — to promote Abdullah’s removal. They convinced the then Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, against his better judgment to do so. For two decades after that, New Delhi rigged elections and appointed its own proxies as Chief Ministers, eroding the Kashmiris’ faith in Indian democracy.

The Indira-Sheikh agreement of 1975 augured a new beginning by reaching a compromise on the autonomy issue and bringing Abdullah back to power. Free and fair elections held in 1977 confirmed this outcome. Unfortunately, after Abdullah’s death in 1982, the Centre, and especially Rajiv Gandhi, actively destabilised Kashmir by forcing Farooq Abdullah, who had succeeded his father, to relinquish power. It then coerced the National Conference into a shotgun marriage with the Congress, thus drastically eroding the legitimacy of the National Conference, the moderate face of Kashmiri sub-nationalism, in Kashmiris’ eyes.

The openly rigged 1987 election was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Undertaken to diminish the anticipated electoral performance of the opposition Muslim United Front (MUF), it had the opposite effect by forcing many disgruntled supporters of the MUF first to take to the streets and then, from 1990 onwards, to take up arms. Pakistan, unsurprisingly, fished in troubled waters by infiltrating ISI-trained terrorists into the Valley and by training Kashmiri militants to attack Indian forces. This mayhem further strained the Kashmiris’ relations with the Centre. (From The Hindu)

*Mohammed Ayoob is University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of International Relations, Michigan State University