When government coffers offer no relief, initiatives like ArtMatters aim to bring artistes together to help a crippled art community.

French artist Henri Matisse had once let on that creativity takes courage, while according to German-American writer Charles Bukowski this courage was to come from the belly. But will any art remain if the belly is empty? Artistes would rather die than beg, and the COVID-19 pandemic has ensured both. The lack of work and deteriorating financial situation compelled artistes to take extreme steps. TV actors Manmeet Grewal (Kuldeepak) and Preksha Mehta (Crime Patrol) committed suicide. Ashiesh Roy (Sasural Simar Ka) checked out of a hospital because he couldn’t afford dialysis. Solanki Diwakar (Dream Girl) was seen selling mangoes in Mumbai’s Bandra. And Agneepath 2 and Mangal Pandey actor Rajesh Kareer put out a video on Facebook asking for Rs 300-500 to go back to his hometown in Punjab to find some work.

As some European governments announced bailout packages for artistes, in India, the lot was bypassed in the Rs 20-lakh-crore economic-stimulus package that was enumerated by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman last month. The pandemic, which has gone on for a while, has forced them to stare at the gaping chasm between the haves and the have-nots, even within the community.

Event and Entertainment Management Association president Sanjoy Roy was stumped at a Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry meet when he was asked why artistes needed money, that they should instead donate to the government. Roy said he had to explain to them that not every artiste is a Shah Rukh Khan or Sonu Nigam, millions languish in obscurity, from the Bauls, Manganiyars, patachitra painters, craftsmen, and puppeteers, among others.

In rural India, families are dependent on the arts and crafts as primary means of livelihood, and as a secondary mode of income, especially in the agrarian communities. Like the Adivasis in Odisha’s Sadeibareni village who make and sell dokra (bell metal) art in between the two paddy-harvest seasons.

While a plethora of artistes has come forward to help, Roy-led Teamwork Fine Arts Society through its new initiative #ArtMatters, with more than 100 industry leaders and artistes on board, is trying to reach out to the artistes in dire straits. Channelled through its partner organisations across states, it has helped seven craftsmen’s families for a month, provided ration packets to 50 families in a Jaisalmer village, deposited Rs 6,000 for a month’s household expenditure to five (including a folk musician, sattriya dancer and weaver) in Assam’s Jorhat and Majuli, and Rs 10,000 to tabla teacher Ananta Bora who has a kidney-stone operation coming up.

With the help of Kyssa Farms, it has provided 6.3 tonnes of vegetables and grains for the puppeteers and magicians in Delhi’s Kathputli Colony and fundraised for folk artistes like Jaisalmer’s Chugge Khan (of the Manganiyar collective Rajasthan Josh). They are also shooting a concert film, to be out in July, where popular musicians like Kailash Kher and Shekhar Ravjiani will interview folk artistes across the length and breadth of the country.

With the help of Kyssa Farms, it has provided 6.3 tonnes of vegetables and grains for the puppeteers and magicians in Delhi’s Kathputli Colony and fundraised for folk artistes like Jaisalmer’s Chugge Khan (of the Manganiyar collective Rajasthan Josh). They are also shooting a concert film, to be out in July, where popular musicians like Kailash Kher and Shekhar Ravjiani will interview folk artistes across the length and breadth of the country.

“The world was moved by the migrant workers walking homewards, but there’s also a huge section of people who are equally anonymous, equally without their voices to articulate and lobby against their plight,” said Dastkar founder Laila Tyabji in the recent #ArtMatters virtual meet, moderated by Roy.

The other panellists included Dadi Pudumjee, Ishara Puppet Theatre founder and president of UNIMA (Union Internationale de la Marionnette, which celebrates its 90th year this year, with presence in 91 countries), Kathak dancer Aditi Mangaldas, and Jehan Manekshaw, founder-director of Theatre Professionals (he acted in Dhobi Ghat).

“The craftspeople don’t fit into the MSME category, which the government is, I believe, going to support. They are out of the security blanket, have no salaries, provident funds, or insurance. Now they don’t have the market, most of their orders have been cancelled. Even after the lockdown is lifted, people won’t rush to open bazaars and haats to buy the ‘non-essential’ crafts.

While we have to sell the stock they already have since their orders have been cancelled, perhaps, try a ‘pay now, get later’ scheme online, we have to think of an alternative,” said Tyabji, whose four-decade-old Dastkar has provided supplies to 2,000 families across 11 states during the lockdown. Talking about the need for a database for all artistes and artisans, she said that unlike “the government figure of 10-11 million craftspeople, our findings estimate about 200 million people – including the craftsperson’s families and ancillary workers.”

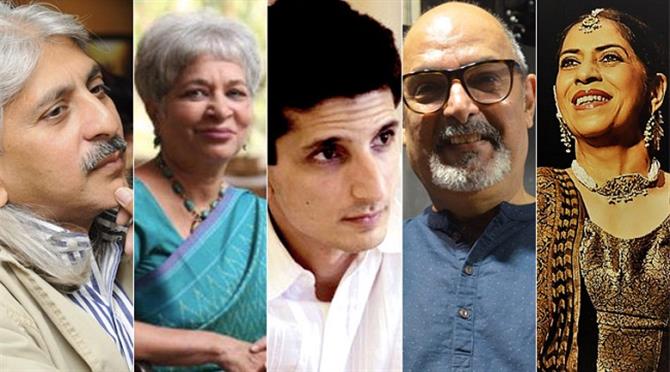

(L-R) Sanjoy Roy, Laila Tyabji, Jehan Manekshaw, Dadi Pudumjee, and Aditi Mangaldas. (Photo: Teamwork Fine Arts Society)

“In the performing arts: theatre, dance, puppetry, music, etc., the Akademi already has a huge database,” added Pudumjee, the past member of the general council of the Sangeet Natak Akademi, “If they are not being able to use it, then there’s something wrong.”

During the discussion Pudumjee spoke about puppeteer groups in West Bengal – their mudhouses washed out by the recent cyclone – have been reaching out to Ishara Trust. “The Akademi needs to reach out and help, which is their mandate,” he adds, “They are trying to do webinars, etc., but what is that getting into the individual artiste’s pocket?” he asked. “No money is coming from the Akademi, from the Ministry of Culture. Artistes who have salary/production grants, who have come for review to Delhi in the last two-three years, some of them still haven’t got that money. Maybe if that is released, those groups can get some sustenance.”

Malwa tradition Kabir folk singer Kaluram Bamaniya received a call from SPIC MACAY a few days ago assuring him of his pending payment of Rs 25,000-30,000 from shows in January. With the opening up of religious places, his performances might also resume soon.

Mangaldas, however, isn’t hopeful. “Auditoriums and theatres will be the last places to open, not two-three months, it will take years, what dance is going to remain within?” she asked. Adding how individual artistes like Shubha Mudgal, Milind Srivastava, TM Krishna have come forward to help, she urged the academies to step in. “We are the people who are sent as the country’s heritage and culture ambassadors, where are you now when we need you? What is the Sangeet Natak Akademi doing with its funds allocated for festivals? What is the ICCR (Indian Council for Cultural Relations) doing with the funds that is meant to send troupes abroad?” asked Mangaldas, who has collaborated with a Swiss museum, a theatre, and currently with Raw Mango to raise funds. “We are not begging. We are offering artistic experiences. The few art initiatives online – by privileged artistes like us – are only keeping sanity for a few, rest are decimated, there’s no food, no performances in the next year. Hundreds of classical dancers don’t have internet access, a laptop, smartphones,” she said.

Manekshaw and other theatrewallahs have been trying to raise funds to help theatre artistes – not just the virtuosos, but the stagehands, sound, lights and props people, tailors, dressmakers, etc. He isn’t optimistic about the government’s “ability to respond” adequately, adding that his greatest learning in this pandemic/lockdown has been “how not to keep all our eggs in one basket”.