One of the enduring images of the Golden Temple in Amritsar is of the glowing shrine at night, its shimmering reflection appearing like liquid gold in the Sarovar or holy tank that stretches out in front of it. It is therefore impossible to imagine the temple without its lights. When they are switched on at night, they not only highlight the temple’s magnificent architecture but also cast an ethereal glow on the spiritual centre of the Sikhs.

Yet, introducing electricity to the Golden Temple or Sri Harmandir Sahib marks a tumultuous chapter in the shrine’s history. After the idea was first proposed in the late 19th century, it sparked a raging war that divided the Sikh community down the middle and even saw some unflattering name-calling.

The controversy was so intense that the standoff lasted more than two decades. Eventually, when the temple complex was properly electrified, most homes in the city of Amritsar had already been using electricity for 13 years!

Before the Golden Temple was electrified, the shrine had been lit up in traditional ways. The sanctum glowed in the light of earthen lamps or diyas, day and night, and the parikrama or pathway around the temple was marked by candlelight. Sikh scholar Udham Singh says in his book, Report Sri Darbar Sahib (1926), that during the latter half of the 19th century, two sewadars or volunteers carrying silver plates with lit candles on them would position themselves next to the granthi Singh or scripture reader, who could then read the Hukamnama hymn from the Guru Granth Sahib.

After electricity was brought to Amritsar, it wasn’t long before a proposal to electrify the Golden Temple was tabled by the Sri Guru Singh Sabha, a Sikh-revivalist organisation set up in 1873 to oversee the transition of control of gurdwaras from the Udasi Mahants or priests to Sikh bodies. The organisation was also tasked with supervising the overall functioning of the Golden Temple, and it tabled its radical proposal at a meeting on January 23, 1896.

However, after electricity was brought to Amritsar, it wasn’t long before a proposal to electrify the Golden Temple was tabled by the Sri Guru Singh Sabha, a Sikh-revivalist organisation set up in 1873 to oversee the transition of control of gurdwaras from the Udasi Mahants or priests to Sikh bodies. The organisation was also tasked with supervising the overall functioning of the Golden Temple, and it tabled its radical proposal at a meeting on January 23, 1896.

It was argued that electrifying the temple would not only enhance its beauty but also benefit the elderly and others who visited it late in the evening or the wee hours. The proposal found support among some members, including Colonel Jawala Singh, who had been appointed as one of the 11 members of the general committee of the Harmandir Sahib by the government.

Many influential Sikhs like Baba Khem Singh Bedi, a direct descendent of Guru Nanak Dev Ji, a businessman Sujan Singh from Rawalpindi, and Balwant Singh from Attari too gave their consent. Then, under Sardar Arjan Singh Chahal, an 11-member committee was set up to oversee the installation of electricity in the shrine complex.

The next step was to raise funds, so appeals were made in towns and villages for contributions towards this ambitious project. But the money raised wasn’t enough and they needed the support of the financially powerful, and who would be better to finance them than the kings of princely states! Thus, a delegation was sent to Raja Bikram Singh of Faridkot who assured them of financial support.

On April 25, 1897, representatives of the Raja told the Akal Takht, the highest religious authority of the Sikhs, that the Raja would contribute Rs 20,000 towards the temporary installation of electricity in the Harmandir Sahib, during the celebrations of the diamond jubilee of Queen Victoria as the English monarch. If all went well, the Raja would then consider funding the permanent electrification of the temple complex.

Immediately, sparks began to fly and the debate around the electrification of their holiest shrine divided the Sikh community into two camps. Accusations were hurled, voices grew ever louder and there was much name-calling. Traditionalists even called the supporters of electrification ‘bijli bhakts’.

Hoping to put an end to the raging debate, in May 1897, three granthis or scripture readers of the shrine served a notice on the 11-member ‘lighting committee’ coordinating the issue, opposing the electrification proposal. It didn’t work.

On June 22, 1897, the diamond jubilee was observed in the Harmandir Sahib complex, where Prince Gajendra Singh, son of Raja Bikram Singh, was present. The temporary electrification had indeed gone through and electric bulbs were installed in a small area in the complex. They were powered by a private generator belonging to a wealthy banker from the city, Lala Dholan Dass. It was a historic moment – for the first time, electric lights were switched on in the holiest of holy gurdwaras.

But the mood was far from celebratory. While members of the Sri Guru Singh Sabha in Amritsar gloated over their ‘historic achievement’, the Lahore unit of the Sabha was furious at the development. On July 29, the executive committee of the Lahore unit officially recorded its disapproval with the lighting committee.

Even the high-profile Punjabi newspaper, Khalsa Akhbar Lahore, published a scathing editorial dated 6th August 1897, criticizing the use of electricity in the Harmandir Sahib. The editorial said that the Sikhs needed the light of the Guru’s blessings, not the invention of electricity. It added that the Harmandir Sahib wasn’t a museum that needed such novel displays and went on to add that, unlike traditional ghee diyas which could be used any time, electric lights would be subject to electricity cuts, which would disrupt the functioning and prayers in the shrine.

Neither was the Raja of Faridkot nor the Amritsar unit of the Sri Guru Singh Sabha moved. Raja Bikram Singh went one step further. When he visited Amritsar on 14th August 1897, he was told that those who had attended the diamond jubilee function at the shrine were so fascinated by the glowing Harmandir Sahib that they wished they could see it lit up again.

Standing in the courtyard of the temple complex, the Raja announced with much fanfare and drama, that as long as the Harmandir Sahib was denied electricity, his palace too would remain in darkness. Leaving everyone speechless, he announced a donation of 1 lakh rupees so that the much-feared innovation of electricity would be brought to the Golden Temple. The money was to also cover the costs of a new building for the Guru ka Langar or common kitchen of the shrine.

It was now an all-out war. The Khalsa Akhbar Lahore published another editorial, dated 20th August 1897, which while praising the Raja of Faridkot for his donation but did not spare those who had advised him to pledge the money. In the newspaper’s 27th August 1897 issue, three granthis of the Harmandir Sahib published a letter attacking the electrification proposal. Citing numerous accidents involving power lines and electric circuits in America and India, they pointed out that electricity posed a serious risk to life and the Harmandir Sahib itself.

Another article in the same issue of the newspaper pointed out that neither had the houses of worship of the Christians nor the Muslims been lit up with electric lights “in Bethlehem or Kaaba”, and “not one of them over 1,500 churches in London had been electrified, not even in Westminster Abbey”.

Some leading lights of the Sikh community made a much more poetic argument against a “useless extravagance” such as electricity in the Harmandir Sahib. It was also argued that electricity could dazzle the devotees and distract them when they prayed.

The advocates of electricity realised that they were not going to win this battle as the opposition had many influential Sikhs, including the granthis and custodians of most gurdwaras, on their side. Thus, for the next two decades, the traditional ghee lamp prevailed.

But the future began to look bright again, in the early 1920s, when the Akali Movement or Gurdwara Reform Movement, the political wing of the Sri Guru Singh Sabha, officially handed over control of the gurdwaras from the Udasi Mahants to a new Sikh body called the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), which controls the functioning of gurdwaras even today.

Interestingly, Sardar Sundar Singh Majithia, the first prominent individual to argue in favour of the introduction of electricity to the holy shrine, became the SGPC’s first President in 1920. Besides, in the past two decades, the people of Punjab had begun to accept a more modern outlook to life and there was a new wave in favour of electrifying the Harmandir Sahib. This time, it didn’t flicker out like a candle in the wind.

Sikh scholar Giani Kirpal Singh mentions in his book, Sri Harmandar Sahib Da Sunhari Itihas (1991) that after important Gurdwaras in Amritsar, including the Shaheed Ganj Baba Deep Singh, Ramsar Sahib and Bibeksar Sahib, allowed their shrines to be lit up by electric lights in 1929, the following year, the Harmandir Sahib invited that much-despised, even ‘risky innovation’ into its holy precincts.

And where did they get the funds to execute the project? The money pledged by Raja Bikram Singh of Faridkot more than two decades earlier was finally withdrawn from Punjab and Sindh Bank! The Raja’s wish was finally being fulfilled. The records of the Harmandir Sahib state that the money was used to purchase all the electricity generation equipment and raw materials that were needed.

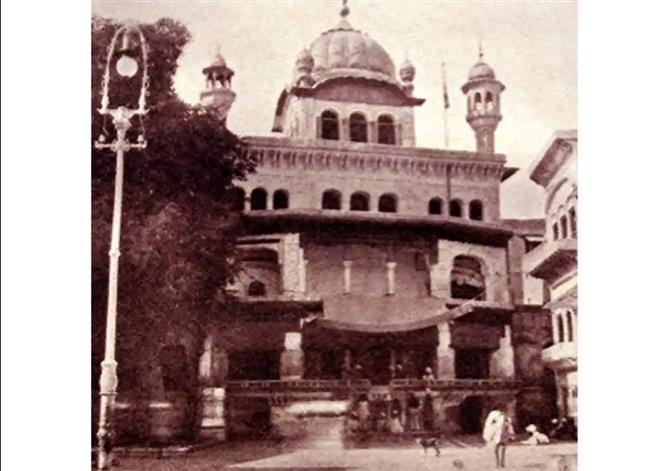

A new era had been ushered in for the Golden Temple. To light up the complex, electric poles connected by electric wires were installed at various places, including the four corners of the Sarovar, and various points in the parikrama of the shrine. One pole was placed between the Akal Takht Sahib and Darshani Deori Gateway of the Harmandir Sahib Sanctum; two were placed in front of the northern and southern gateways, and the last was near the Ath Sath Tirath platform in the parikrama. When these lights first went on, in one swift action, the candles and diyas were extinguished forever.

Starting in 1943 and continuing over the years, many structures in the shrine complex, including the bungas or large mansions were demolished to make way for larger numbers of pilgrims and devotees. Among the many renovations carried out, the electrical system that lights up the Harmandir Sahib too has been upgraded.

But, in a fitting, sentimental gesture, the poles originally installed at the four corners of the Sarovar have been left untouched.